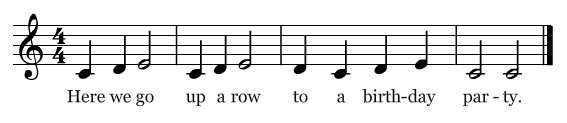

In my family, everyone (except my father) was required to take piano lessons. When I came of the age to begin this process, the teacher of choice in our small town was Brunhilda French, whose maiden name was Wagner and was alleged to be a close relative of Richard Wagner. A graduate of the Eastman School and of the New England Conservatory, she was, I have always been told, a wonderfully gifted musician and a marvelous teacher. I only remember that she was very old and thin, spoke with a very “cultured” accent, and was much more enthusiastic about the songs I played than I was. The only song I remember playing was that old favorite “Here we go up a row” which I have reproduced here in case you would like to learn it too…

Brunhilda was born in 1897, so I suppose she was really only in her late 60’s when I studied under her. I took my lessons in her very old Victorian house high on the East hill. The house was stuffed with very old maroon velvet chairs, dark oaken cabinets, dim oil paintings and other historical artifacts. I don’t remember her piano at all, but high on the wall to its right hung a large and very old and dim painting of Jesus knocking at the heart’s door, which I studied (with more interest than I ever studied piano) while Brunhilda and my mother chatted after my lessons.

Unfortunately, Jesus’ watchful eye did not move me to any real diligence at the piano and I stubbornly resisted becoming a virtuoso. Though I can’t remember any of the music beyond “Here we go,” I think I took lessons for a year or two, until my exasperated mother yielded to my endless complaints. She would later describe receiving the revelation that “she was trying to make a silk purse of a sow’s ear” though she never meant to imply that I had no musical potential. Nevertheless, the comparison to a sow’s ear somewhat weakened my confidence with regard to musical greatness.

When my first son was old enough to take lessons and there was once again a piano in the house, I set out to prove I was no sow’s ear, and spent several months practicing Beethoven’s “Fur Elise” until I could play the whole thing by memory without mistakes and at a reasonable tempo. It was actually thrilling to make music like that flow from my own fingers and for the first time I had a hint of why folks are willing to invest all those hours of practice. But the investment I had made in “Fur Elise” was pretty steep and I didn’t repeat it. Now and then, I would try to play a few hymns, but the silk purse never materialized.

When my first son was old enough to take lessons and there was once again a piano in the house, I set out to prove I was no sow’s ear, and spent several months practicing Beethoven’s “Fur Elise” until I could play the whole thing by memory without mistakes and at a reasonable tempo. It was actually thrilling to make music like that flow from my own fingers and for the first time I had a hint of why folks are willing to invest all those hours of practice. But the investment I had made in “Fur Elise” was pretty steep and I didn’t repeat it. Now and then, I would try to play a few hymns, but the silk purse never materialized.